Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

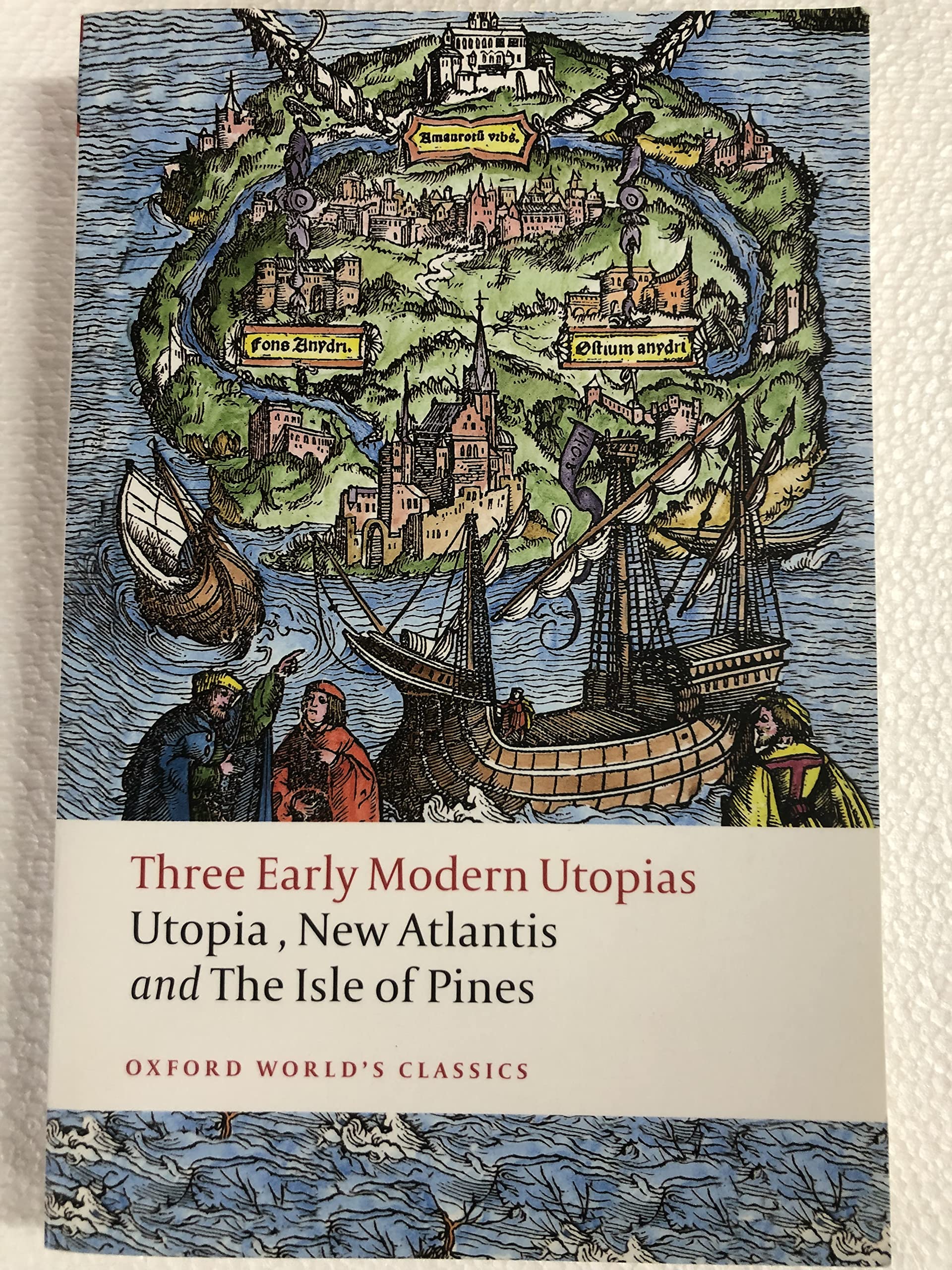

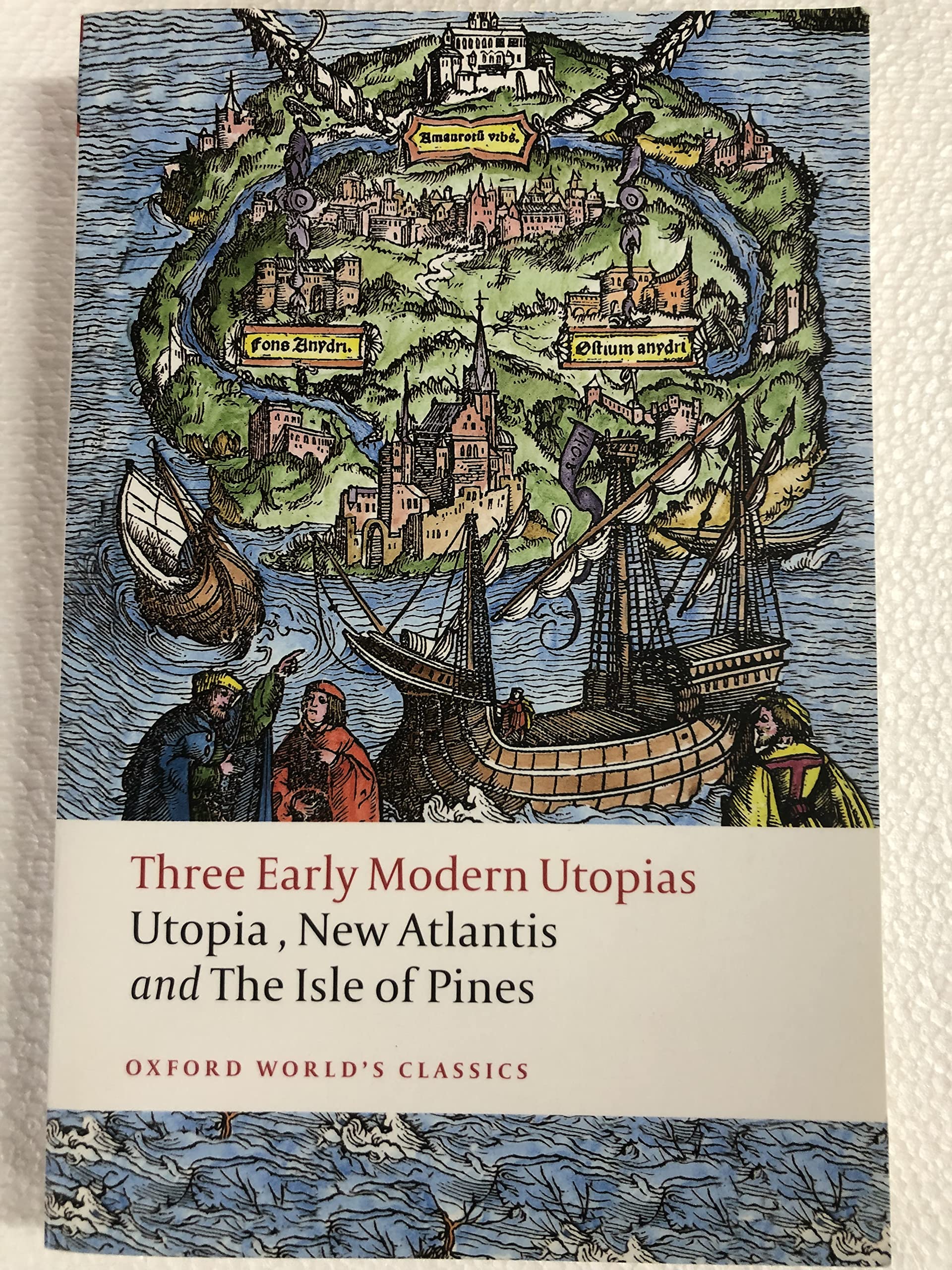

Three Early Modern Utopias: Thomas More: Utopia / Francis Bacon: New Atlantis / Henry Neville: The Isle of Pines (Oxford World's Classics)

Trustpilot

1 month ago

1 week ago

1 day ago

3 days ago