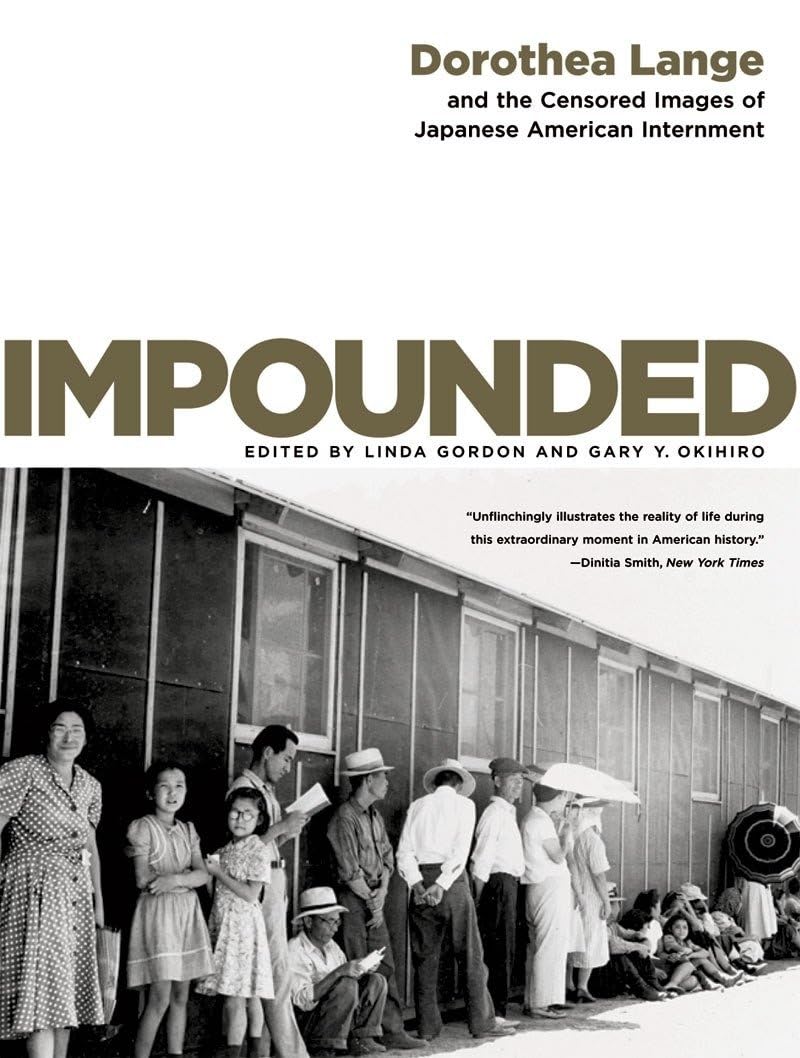

Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

K**S

shrewd photography that makes the viwer think

The terrible injustice of Japanese-American dispossession and internment during WWII is very clear and provokes thought. Plus, there's a kind of conversation going on with the photographer: Ms. Lange, did you choose to highlight these words on a box so I'd go on and think X and Y? Are you hoping I can imagine on my own a bigger scenario here? The book is worth pondering and re-pondering.

D**N

It Can Happen Here. FDR's Day of Infamy.

To our nation's everlasting shame, FDR on February 18, 1942, ordered the roundup and incarceration of some 110,000 Japanese Americans, well more than half of them U.S. citizens and life-long residents. They were given barely more than enough time to pack a tooth brush and a change of underwear before they were forced to leave their homes. They were denied the opportunity to prove their loyalty to their country. Thus did FDR respond to the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor ("a date that will live in infamy") by an infamous action of his own against his own people. But for Dorothea Lange's remarkable photographs of this egregious episode in our racist past (German and Italian Americans were treated with much more deference), we would have a far less meaningful record of the wrongs visited on Americans of Japanese ancestry. The story of how the photographs came to be taken is told in the first of two long chapters of "Impounded." The second long chapter is an account of the "profound effects in the Japanese American community" of its members long internment in what were barely more than concentration camps. First published five years ago, some 65 years after the events portrayed, Lange's photographs reveal her sympathy for her subjects. One will search the photographs in vain for any evidence that these Americans either singularly or as a group posed any threat to our security. Not one of pictures could, by any stretch of FDR's war driven imagination, be used to show that the internment program was justified. No wonder, then, that the government suppressed their publication, impressing the word "impounded" on the prints. "Impounded" tells two stories, both important to our understanding of the period. The first, the one told in the photographs, is that of the nature of, and the effects of, the unjustified deprivation of the civil rights on an entire subset of the American population. The second story, unspoken except by implication, is of the government's acknowledgment of the wrongs committed by its need to impound these photographs. Linda Gordon and Gary Okihhiro, the editors of "Impounded", demonstrate just how fragile our liberties are and how much is required of us all to prevent their erosion by our government. It can happen here. End note. An earlier review by Rollin Drew sharply criticizes the publisher for the inferior quality of the book's reproductions of Lange's extraordinary photographs. He may well be right as a technical matter. But on the level at which this book spoke to me, the quality of the prints amply reveals Lange's remarkable courage in challenging the underlying need for the relocation program and by showing the scarring hardships it imposed on our fellow citizens. See if you don't agree.

C**N

Very good shape and well packaged

There’s a little bow in the front hardcover but the book is otherwise in excellent shape, including the dust jacket. Shipping was prompt.

J**.

Every American citizen should get this book

How many people know that the US government impounded all people of Japanese ancestry in fenced in, guarded camps, living in conditions that I consider horrible? Even if you've heard this you might not know that Dorothea Lange, a well known photographer, was sent to these camps to show that the interred Japanese were not being mistreated. She followed orders: no pictures of the barbed wire fence, no pictures of soldiers with guns. Nonetheless when the people at the Dept of Defense saw her photos, they impounded them! They did not permit them to be released. For several decades after the end of WWII, after Dorothea Lange had died, they were hidden. Finally they were released to the library of Congress, with no announcement and no fanfare. But they were found and this book was produced. Get it and see what a misguided government policy can do, when fear of foreigners overwhelms rational judgement. With original comments by the photographer.

R**N

An important, but not wholly satisfactory, portrayal of a shameful episode of U.S. history

Perhaps the most racist and unconstitutional program the U.S. government engaged in against its own citizens over the past century was the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. In the first half of 1942 about 110,000 Japanese-Americans - most of whom had been born in the United States and were U.S. citizens, and many of whom had close relatives actually fighting for the country in the U.S. military - were shipped off to ten concentration camps and rather Spartan living conditions in the hinterlands for the duration of the War. This book tells and illustrates much of the injustice of that program, but not in a wholly satisfactory way.As Gary Y. Okihoro writes in his contribution to this book, "As the nation prepared to defend democracy against the threat of fascism, its leaders authorized and conducted undemocratic actions that bypassed and ignored constitutional guarantees and freedoms." It is impossible to justify that irony. The program was conducted pursuant to Executive Order 9066, which Franklin D. Roosevelt issued in February 1942, in the wake of Pearl Harbor. But the seeds of the program long pre-dated Pearl Harbor. One of the sorry facts I learned from Okihoro's essay was that as early as August 1936 FDR was advocating that the military compile a secret list of those Japanese "who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp in the event of trouble." FDR deserves praise for his overall sympathy for the common man and woman, but as regards the Japanese he had a racist blind spot.Based in large part on her famous photographs taken for the Farm Security Administration during the Depression, Dorothea Lange was engaged by the government to document the "relocation" (the preferred euphemism) of the Japanese-Americans. The War Relocation Authority probably hoped that her photographs would generate support for its program, just as her Depression photographs had done for the FSA. But that would have required photographs of happy, smiling, contented incarcerates - subjects hard to find. Plus, Lange refused to be co-opted into promoting a lie. Instead, as a body of work her photographs "challenged the political culture that categorized people of Japanese ancestry as disloyal, perfidious, and potentially traitorous, that stripped them of their citizenship and made them un-American." So the WRA declined to publish the vast majority of Lange's photographs, instead quietly depositing them in the National Archive.IMPOUNDED tells the above tale in three sections. First there is an essay by Linda Gordon about Dorothea Lange that focuses primarily on her work for the WRA. Second is an essay by Gary Y. Okihoro that discusses the history of American discrimination against Japanese immigrants and especially the various manifestations of that racism during World War II. Third is a collection of slightly over 100 of the photographs that Dorothea Lange took in 1942 of Japanese-Americans (a) during the days before the evacuation, (b) being rounded up, (c) living in rather squalid conditions at various assembly centers, and (d) as imprisoned at Manzanar, the largest of the ten camps.Now why do I say the book is not wholly satisfactory? First, as other reviewers have noted, the photographs, as reproduced here, tend to be disappointingly small in size and of middling quality. Some of the more poignant and striking of the photographs can also be found, larger and better reproduced, in "Executive Order 9066" by Maisie and Richard Conrat (which, incidentally, I recommend over this book for those who are primarily looking for photographs of the internment program). Second, both of the authors - Okihoro more so than Gordon - are too tendentious and heavy-handed for my taste. It's a rather small point, and a condemnatory attitude is understandable, but the injustice of the internment program is manifest from any sober, objective recounting of the facts and does not need to be constantly underscored with judgmental cynicism and pathos. I would have preferred that the book left the propaganda to Lange and her more nuanced photographs.

G**N

Great buy

Wonderful read.

M**I

interessante

storico

D**S

Five Stars

It's not about the photographs.

M**N

A gap filler but falls short of its potential

The book is not as well printed as it should have been - so the reproductions of rare Dorothea Lange images are of distressingly mediocre quality. This is a pity. Anybody interested in this period of Dorothea Lange's work will probably feel very frustrated by both their quality and number. The book's two editors/essayists are both historians and write interestingly on Lange's biography and its political context and on the day to day Japanese-American experience, but a third was needed; someone who has a primary understanding of and interest in her images and practice; the book shows the absence of a photographic curator.

Trustpilot

1 week ago

1 month ago